Roy Curtis: Inconceivable loss highlights fragility of life, force of love

Heart-wrenching funeral of crash victims left town paralysed and families distraught

TWO hearses, a town disembowelled by grief, a family staring into an unimaginable void, despair marbled with disbelief.

A tremor of tears, an earthquake of shattering hearts, sinkholes of pain opening to swallow a hushed, weeping congregation, reality shifting, a violent shaking of what lies below the surface, that part of us where our essence – our soul – resides.

A brother and sister – Luke and Grace – two of four young friends stolen by a ruinous moment on a quiet country road, side by side on their last journey, conjoined in their long sleep.

A corner of Tipperary thrashing feebly about in a sludge of incomprehension.

Grace McSweeney

A mother and father enduring an ache, an otherworldly emptiness, that no mother and father should suffer.

This was Friday, black, lightless Friday, on Gladstone Street in Clonmel, a shattered, helpless community doing the only thing it could: Offering itself as scaffolding to hold up the McSweeney family as the world collapsed around them.

On Thursday it had been the funeral cortege of Nicole Murphy inching down streets lined by the bewildered and broken. Yesterday the outpouring of affection was for Zoey Coffey.

Love, of the bone-deep, shared blood, proprietor of the soul variety, is articulated in countless quiet deeds and gestures.

But it is in loss – tragic, inconceivable bereavement – that it announces itself most eloquently, most painfully.

Amid intense heartache, a funeral offers something profound and, yes, beautiful: The untouchable, eternal force of love.

It is evident in this passage from Ellen Coyne’s evocative Irish Independent portrait of Friday’s crushing scenes:

“The twin hearses rolled to a stall in front of the church. The only sound was snapping lens shutters and sobbing.

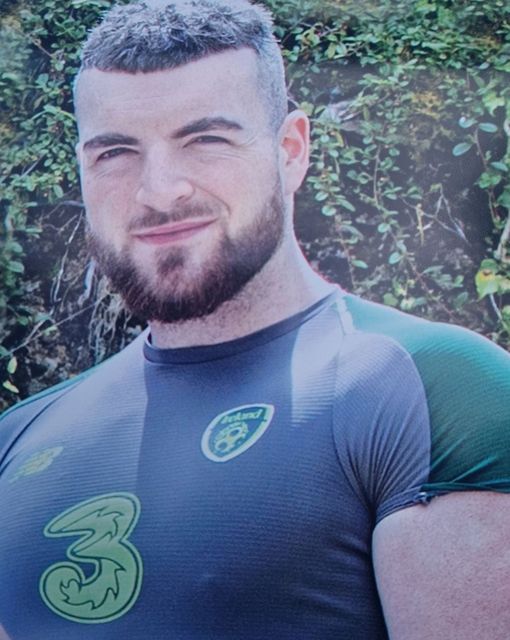

Luke McSweeney

“A daughter in one, a son in the other. Behind one hearse stood a mother, behind the other a father. Paul and Brigid McSweeney were figures of staggering dignity. They stood side by side, two parents facing the coffins of two of their four children. It was the image of utter wrong, a totally unnatural scene. Paul brought a hand to his eye, and swiped one lonesome tear away.”

Read more

Hernan Diaz, the sage Argentine writer recently awarded 2023’s Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, is a font of observational wisdom.

In his debut novel, In The Distance, he notes that “finding bliss becomes one with the fear of losing it”.

How many parents have tossed and turned in their bed, checked their phone or wristwatch a thousand times, waiting for a teenage son or daughter to return from a night out?

Luke was driving his sister, Grace, and her friends Zoey and Nicola, to the bus that would take them onwards to their Leaving Cert result celebrations when everything changed.

Three teenage girls and a strong, vibrant 24-year-old man lost; all their tomorrows washed away.

For the Coffey, Murphy and McSweeney families, a circle of light dims. Normality is obliterated. Bliss is lost.

Nikki, the girl who loved to sing A Million Dreams with her mother, whose own dream was to be a radiographer.

Luke, the larger-than-life family man, the St Mary’s hurler who idolised Conor McGregor; Grace, the shy, sincere sister, whose elegance and refinement as a gymnast and a dancer announced that she was named well.

Zoey, radiant in that photograph where she wears a lovely pink dress, the picture fated, unbearably, to accompany her RIP.ie death notice.

A quartet one moment knowing what Diaz calls “the ecstasy of existence”. And then, gone.

Every shop and business in the town of Clonmel closed their doors for the funeral; but shuttering the heartache, that was an impossibility.

Outside St Peter and Paul’s Church on Friday, the streets were pebbled with young, dazed, stupefied, tormented faces.

The day resembled a shattered vase, a thing of forlorn fragments.

Parents held tight to their own children. An elderly woman blessed herself. Next to her, a man, unable to compute the cruel logic of the unfolding scene, continually shook his head from side to side.

Clonmel itself felt animate, a wounded, disabled, sad-eyed, uncomprehending creature. Like its citizenry, paralysed by incredulity.

From the altar, Brigid McSweeney somehow found the strength to address the mourners.

“Leave your sorrow behind here today,” was her request for her children’s friends, “and make the world a better place.”

Sniffled sobs filled the air and the gift of life felt like a precious and fragile thing.

.jpg)

.jpg)