Those forgotten Irish emigrants who became our Nowhere People

The stories of those who left for England will finally be told in a new oral history project

They are the largely forgotten Irish, so many of their number lost to whiskey and loneliness and shame, falling between the cracks in London or Birmingham or Coventry.

We speak of the navvies who rebuilt Britain in the post-war years, working back-breaking shifts on road and railway, drinking all they could swallow until the early hours.

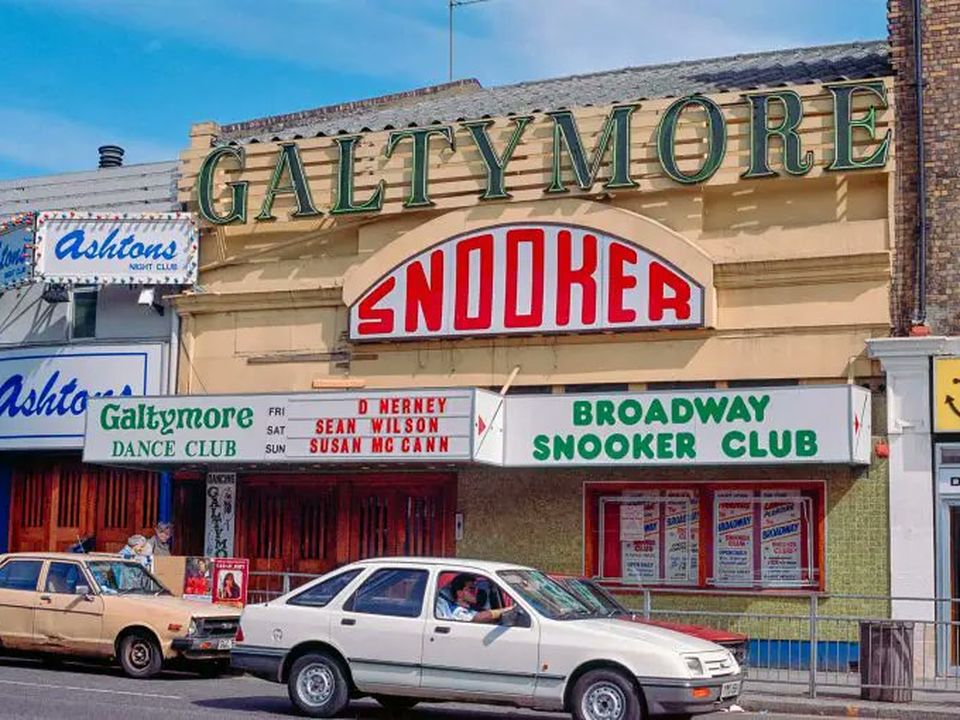

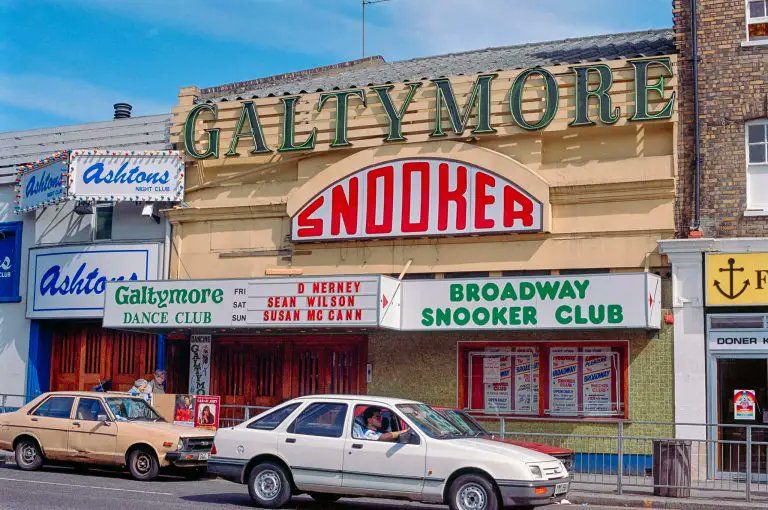

They spilled into the Galtymore in ‘County Kilburn’ on Saturdays, to dance to Joe Dolan or Big Tom, to find a wife, to reminisce, to remember and to forget.

Through the mid to latter decades of the 20th century, a symphony of Mayo, Donegal and Kerry accents played as the music of everyday life, the Irish becoming part of the contours of Cricklewood, Shepherd’s Bush and Camden.

Poverty

In 1961, the Irish population in England and Wales peaked at 681,000, generation after generation of McAlpine’s Fusiliers signing up for long, hard hours of labouring work.

Life was not easy for many of Ireland’s emigrants

A fraternity of refugees fleeing the poverty and hopelessness and social oppression of their homeland.

Night after solitary night, they sat on high stools in O’Reilly’s of Kentish Town, the Archway Tavern, The Crown in Cricklewood and found a little piece of home.

Bulwarks against despair, sanctuaries where, even if they were on their own, they were not alone.

Many married and advanced a few rungs and more up the economic ladder, living happy and fulfilling lives, opening businesses, making fortunes, establishing themselves as community pillars.

Many others, unable to get themselves together, stuck in a moment, were not so fortunate, succumbing to a crushing kind of desolation, helpless as the walls closed in.

On Sunday they listened to Michael O’Hehir on the wireless; at closing time they stood for Amhrán na bhFiann. Then, they stumbled to their draughty bedsit, only the wind for company.

Reminded of their place in London’s hierarchy by the pitiless signs in the lodging house windows: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs.

They were the Nowhere People: Neither home nor abroad. Neither here nor there.

Addiction, homelessness, humiliation, guilt, heartache, a dismal solitude, the demons came hard, fast and unrelenting.

Ralph McTell’s heart wrenching but beautiful Streets of London had so many of those lost Irish, the human detritus cast into the social gutter, among its subjects.

‘Have you seen the old man

In a closed down market?

Kicking up the paper

With his worn-out shoes

In his eyes, you see no pride

And held loosely at his side

Yesterday’s paper

Telling yesterday’s news.’

For too many of these broken creatures the sun stopped shining even as their hearts beat on, their lives little beyond a frigid void, no more in control of their destiny than the flotsam in the dark December Thames.

Too ashamed to take the boat home, abashed and humiliated, they disappeared into the fissures of the city.

Some maintained a pretence, sending letters and money home even as they relied on the life-raft of the local Irish Centre to keep them afloat and put a little food on their own plate.

Many of them grew old and died alone, their accents and the tattered family photograph in their pockets the last reminders of who they were, where they came from.

Now, at last, they are being remembered, their stories pulled from the rubble, resuscitated and brought back to life.

Look Back to Look Forward: 50 Years of the Irish in Britain is an oral history project that aims to reflect the diverse experiences of Irish exiles over the last half century.

The Irish in London and beyond are a changing demographic, diminishing in number though rising in status, the exiles now laden down with highly educated young professionals, doctors, lawyers, well remunerated tech and financial sector workers.

Many of the old pubs that offered a social crutch to the new arrivals have been shuttered, others have morphed into Polish bars or hipster coffee houses. The Galty’ closed in 2008. The Irish in Cricklewood are largely elderly.

Census

In the most recent census, the number of Irish in England and Wales was down to 324,670. Once the largest ethnic group born outside the UK, they have fallen to fifth, behind the Indians, Poles, Pakistanis and Romanians.

Look Back to Look Forward has so far spoken to more than 100 immigrants and second- generation Irish, piecing together the tapestry of life in the big cities long ago.

And giving a voice to the too long unheard.

To those who came in their droves from the villages and rural West of Ireland byways, lured by dreams that often darkened, reduced to forgotten specks in the potholes of London life.