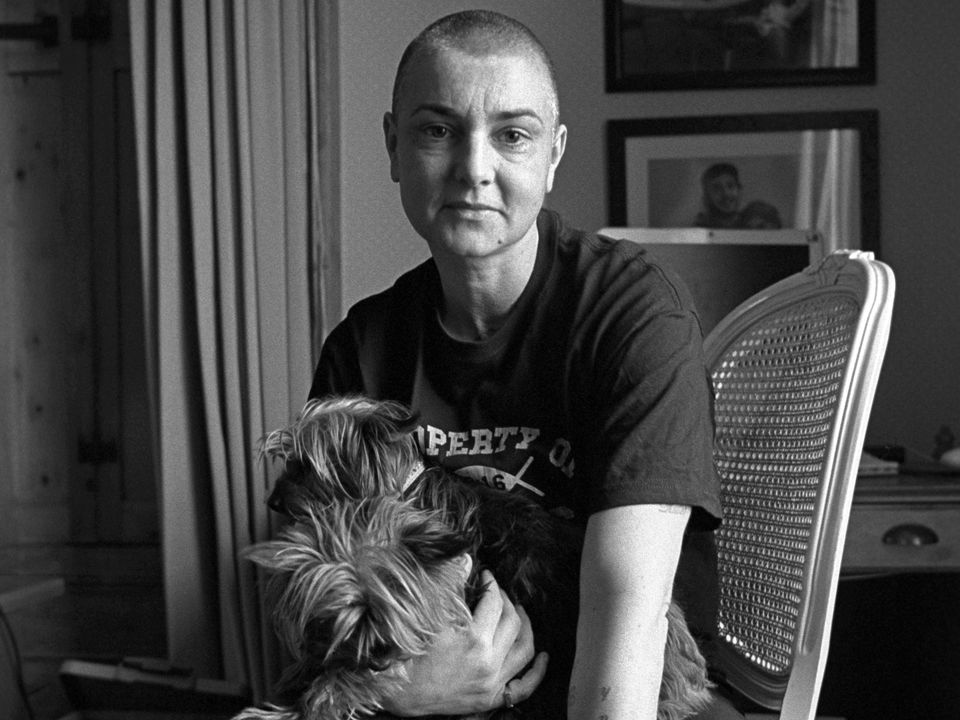

Roy Curtis: ‘Sinéad’s life story was the mother of all struggles...’

Living with her mum was pain-filled, but with the hope that death would reconcile them

Sinéad O’Connor had a complicated relationship with her mother

FROM the forest of sadness, to sprout and entangle the soul of Sinéad O’Connor – none feels more unfathomable.

Sinéad’s own mother pinning her to the floor, pummelling her mercilessly and demanding her daughter – who has curled up in a terrified ball – repeat, again and again, “I am nothing”.

Picture yourself as that broken, sobbing child, every atom of innocence and self-regard pilfered from your being.

It must be a kind of psychic Armageddon, the mental equivalent of the deadly payload from the atom bomb that did for Hiroshima being dropped on your young, fragile heart.

How could anybody ever withstand the fallout, ever hope to recover, from such emotional annihilation? I guess the answer is they couldn’t.

A mother’s love is so elemental to all we become, that warm blanket of unconditional affection acting as a blessed maternal shield from the chill of the big, bad outside world.

Denied the oxygen of that life-affirming tenderness, the world must become a suffocating and unbearably lonely hellscape.

A haunting kind of self-loathing always seemed to co-habit with Sinéad’s genius, anger, irreverent humour and beauty.

She could be at once larger than life and tiny, assertive yet afraid.

How could it be otherwise?

A mother-child relationship plays such an integral role in shaping the adult. When that connection short-circuits, when the child knows only dysfunction, the effect must be devastating.

Sinéad’s brother, Joseph – literary titan, author of, amongst others, My Father’s House and the towering Star of the Sea – is a kind of hero to your columnist, his fertile, wordsmith’s mind yielding an impossibly abundant harvest of lyrical, wise, gorgeous sentences.

His sister, too, could write and when she did her hunger for love and affection – the emotional food and drink of which she was for so long starved – was insatiable.

It is a thread running through her sharp and self-deprecating memoir, Rememberings, where she vividly describes those grotesque childhood beatings.

Equally graphic are her words and frightened body language, the familiar tattooed superstar again a vulnerable fledgling, in a 2017 TV interview with Dr Phil.

Read more

Recounting her relationship with her alcoholic mother, Marie, who was killed in a car crash when Sinéad was 18, O’Connor’s words are unsparing.

“She kicked the s**t out of me. She won’t change her clothes. She won’t wash. The same for us, five years of living in the same clothes. No washing.

“She won’t heat the house. She won’t get lights. She won’t stop taking drugs.

“She never tells me I’m pretty. She never tells me I’m sweet. She makes my brother scream. She smells. There was a smell about her that was sickness. The smell of evil, you know.”

Speaking those words, she is a porcelain vase, a fragile infant wishing to be held, craving that emotional umbilical cord so many of us take for granted.

I write a lot about my late mother, a selfless creature, a bottomless well of love from which my brothers and I could ladle great, soothing draughts of kindness from dawn to dusk.

Sinéad’s experience was at the opposite end of the bandwidth.

The sum of all a child’s fears.

You don’t have to be a descendant of Freud to recognise that such a grotesque opening chapter to a life story must be the catalyst for so much of the darkness that ensued.

Those of us who, as children, never had to worry about our place in our mother’s affections, yearned for bikes and toys and trips to McDonald’s.

A ravenous Sinéad – as she details in that 2017 audience with Dr Phil – hankered after a literal Happy Meal.

Asked what she craved from her mother, she delivers a heart crushing response: “Cuddles, love, kisses, sweet names, snuggles.”

Instead, she found herself plunged into an emotional acidic bath.

“Kicking me, kicking me, kicking me, kicking me and kicking me. And telling me I’m evil and telling me I shouldn’t have been born and the reason my father left is my fault.”

This is the burden that Sinéad O’Connor carried, for 56 years, in the backpack of life.

The pain – the bone-deep torment, the thirst to matter to somebody else – is everywhere in the fury and tenderness and fathomless depths of that extraordinary singing voice.

There is a deeply moving, almost unendurably touching moment in the TV interview where, despite everything, or maybe precisely because of it, she reveals her longing to be reunited with her mother.

“I cannot wait until the day that I naturally get to Heaven so that I can see my mother again. I’d throw myself on her like a monkey and I’d never let go. I’d tell her ‘I love you, I love you, I missed you so bad.’

“My life has been terrible, terrible, terrible. I miss her so bad. I can’t wait to see her again.”

I have never read anything quite like those last two paragraphs, a beautiful, overwhelming, desirous river of heartbreak.

One in which a wounded, exhausted creature swum as best she could.