Sean McGoldrick: ‘Over eleven days covering 126km we climbed 8,000ft’

Our man Sean takes on the arduous trek to Everest Base Camp and experiences an incredible landscape with newfound friends

Scoffing down boiled potatoes and soup at half eleven in the morning under a blazing Nepalese sun is not the archetypal holiday moment. But as Kerry based explorer Pat Falvey kept reminding us, our journey was an adventure not a package holiday.

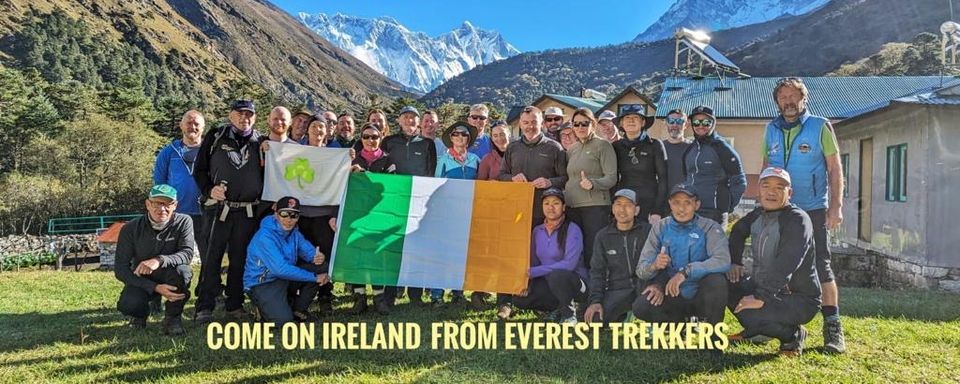

Last month he led a group of 24 trekkers, six Sherpas and 14 porters to Everest Base Camp, a bleak moon-like plateau, situated at an altitude of 5,364 metres (17,598 ft) which is six times higher than Carrauntoohil, the tallest peak in Ireland.

Reaching the start of the trek in Lukla is an adventure in itself. Unless you have money to burn and hire a helicopter, the only realistic option is to travel on a 20-seater plane into Lukla’s Tenzing-Hillary Airport, officially the most dangerous airport in the world.

In her wonderful book ‘In the Shadow of the Mountain’ Peruvian climber Silvia Vasquez-Lavado described the sloping runway ‘as the length of a football field its tiny strip slams into a mountain on one end and plunges thousands of feet into a rocky ravine at the other’.

Sean almost there

There is no radar and once the mist descends the airport which is situated at 2,846m (9,337 ft) attitude all flights are cancelled.

Our group lost two days due to the airport being shut but we were lucky…while trekking the airport was closed for four consecutive days.

Before that flight there was a hair raising five-hour coach journey from Kathmandu to Ramechhap where the bus driver had two assistants, one for sounding the horn and the other for paying the tolls. Let’s just say the Araniko highway makes the Conor Pass in Kerry look like a four-lane highway.

Apart from helicopters, there is no vehicular transport in the Khumbu valley. But there are many mules, ponies, yaks and dzos – a hybrid between yak and local cattle - all of whom wear cow bells and have the right of way on the narrow tracks transport most of the supplies.

Everything else is carried by porters who despite their diminutive physical stature transport enormous 90kg loads strapped to their foreheads.

The group from Ireland led by adventurer Pat Falvey.

After a hearty breakfast in Lukla’s Mera Lodge our intrepid group set off guided by Sherpa Pasang, who has climbed Mount Everest on four occasions and Sherpa Lakpa, one of a handful of female sherpas whose father and four paternal uncles all summited Everest.

As we made and our way across a series of wobbly suspension bridges criss-crossing what locals call the ‘River of Milk’ Valentia Island native Seanie Murphy led the sing-song. It set the tone for the trip of a lifetime.

Over the next eleven days we spent 45 hours and over 300,000 steps covering a distance of 126km. Coping with the high altitude was the biggest challenge as we climbed over 8,000ft in eight days.

Having organised expeditions to Everest Base Camp for decades Pat Falvey is well versed in how to minimise the possibility of being struck by altitude sickness. As the late Noel Carroll said about the marathon it’s not the distance that kills it’s the pace. The same principals apply in the Himalayas.

Sean even got to visit an Irish pub

So, we climbed at a snail’s pace, literally one step at a time, drank up to three litres of water a day as well as hot mango juice, soup, ginger, herbal and black tea and coffee in the tea houses where we ate our meals and slept.

Our resting heart-rate and the oxygen content in our blood was measured twice daily. At sea level the latter is normally 95 percent (less than 92 percent would need hospitalisation).

But at altitude, with low atmospheric pressure, it drops and the body adapts. I averaged around 90 percent for most of the trip, through it did dip to 80 percent on the afternoon we reached Base Camp.

Trekking in the Himalayas is a guaranteed way to lose weight – I shed about six pounds. We ate no meat; not much bread at all and we drank no alcohol on the ascent.

In fairness there was a variety of food available though I never ate so many eggs – boiled, fried, scrambled or in omelettes. There was also porridge, potatoes (boiled, fried or chips), rice, noodles, pancakes and chapatis as well as Dai Bhat, the staple food in Nepalese households consisting of rice, lentil soup and vegetable curry.

Virtually from the moment we left Lukla the scenery was breath-taking. Initially the vegetation was lush with the Rhododendron and Magnolia forest providing a spectacular backdrop to our climb from the village of Phadking to Monjo where we overnighted on Day 1 of the journey.

I roomed with Wexford native Rickie Tyrrell, who had done three high altitude climbs previously. The patter of rain on the tin roof of the tea house kept us awake that night and next day we discovered the hard way that the manufacturers’ boasts about waterproof gear repelling rain doesn’t hold water, if you excuse the pun.

Our destination was Namche Bazar, which marks the entrance to the high Himalayas where the air really starts to thin. It even boasts an Irish bar which we visited for a celebratory drink on the way down.

Next morning the sunshine was back, and we didn’t see rain again until we landed at Dublin Airport.

At every turn we were treated to a new more dramatic skyline best described as ‘granite teeth rising from a thick blanket of fluffy clouds.’

Sean has a celebratory drink in The Irish Pub

The next day the skies cleared and while adjacent to the Tengboche Monastery we finally sighted the summit of Mount Everest. It’s not the most beautiful peak in the range but stands defiant at 29,032 feet amongst the 100 other summits in the Himalayan range.

As the air thinned and the landscape turned into what resembled lunar rock, the conditions in the tea houses became more basic with the dining room heated by a stove fired by dried yak manure.

Between the dust on the trail and the cold in the tea house nearly every member of the group succumbed to sickness. I picked up a chest infection which I’m still trying to shake three weeks later.

But we soldiered on. Finally in the early afternoon of Day 8 we reached Everest Base Camp. It was an emotional moment as hugs and handshakes were exchanged by a group of people the majority of whom had never met until assembling in Terminal One of Dublin Airport eleven days earlier.

There was a sting in the tale. But we had a two-hour hike over rocks before reaching our accommodation in Gorak Shep where we wolfed down the sherpa stew that was waiting for us.

The journey wasn’t over but we knew we had achieved something unique. Far more importantly we had made new friends for life.

As Robert Louis Stevenson said ‘to travel hopefully is better than to arrive and true success is to labour’.

Thanks for the memories.